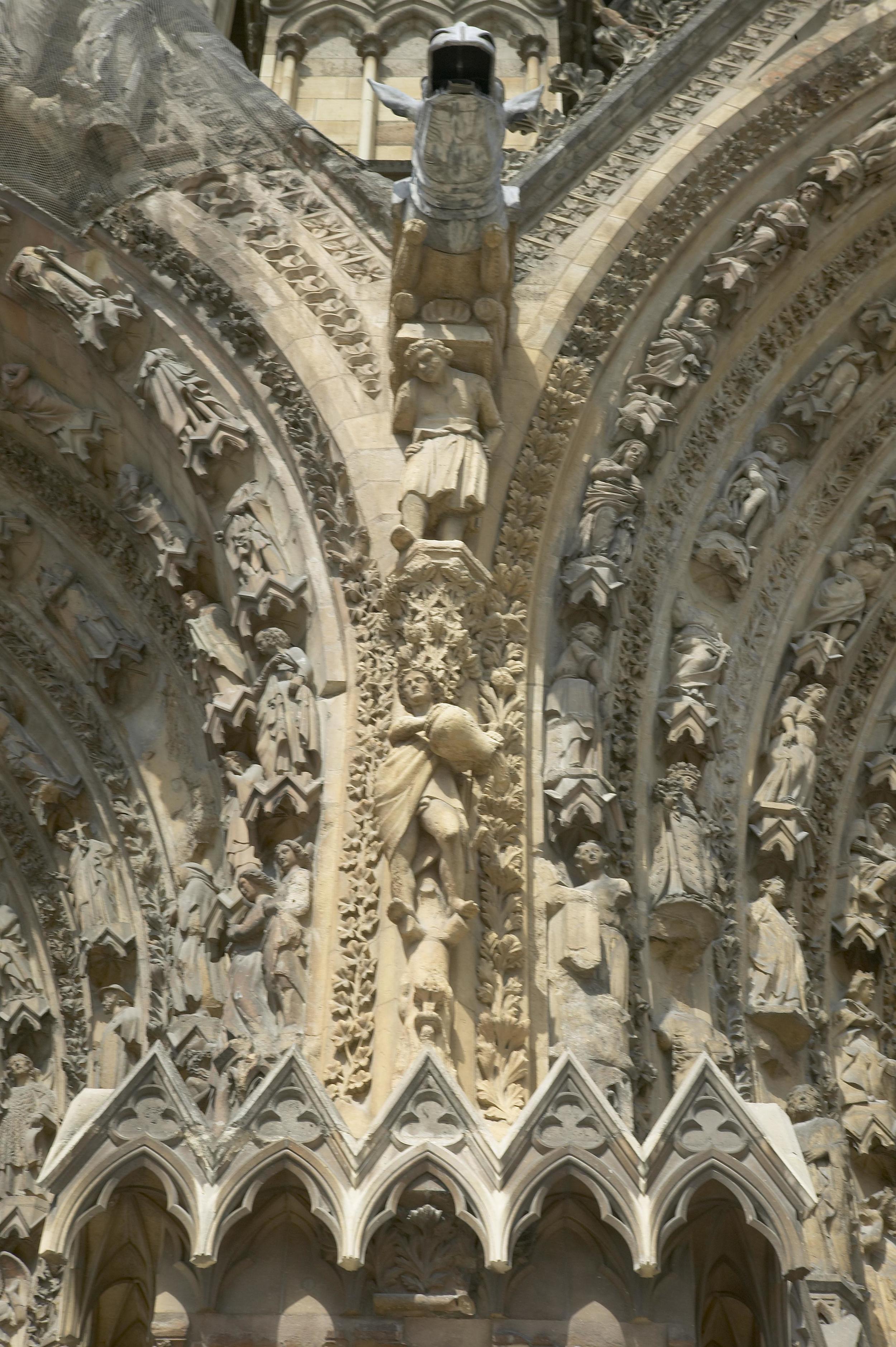

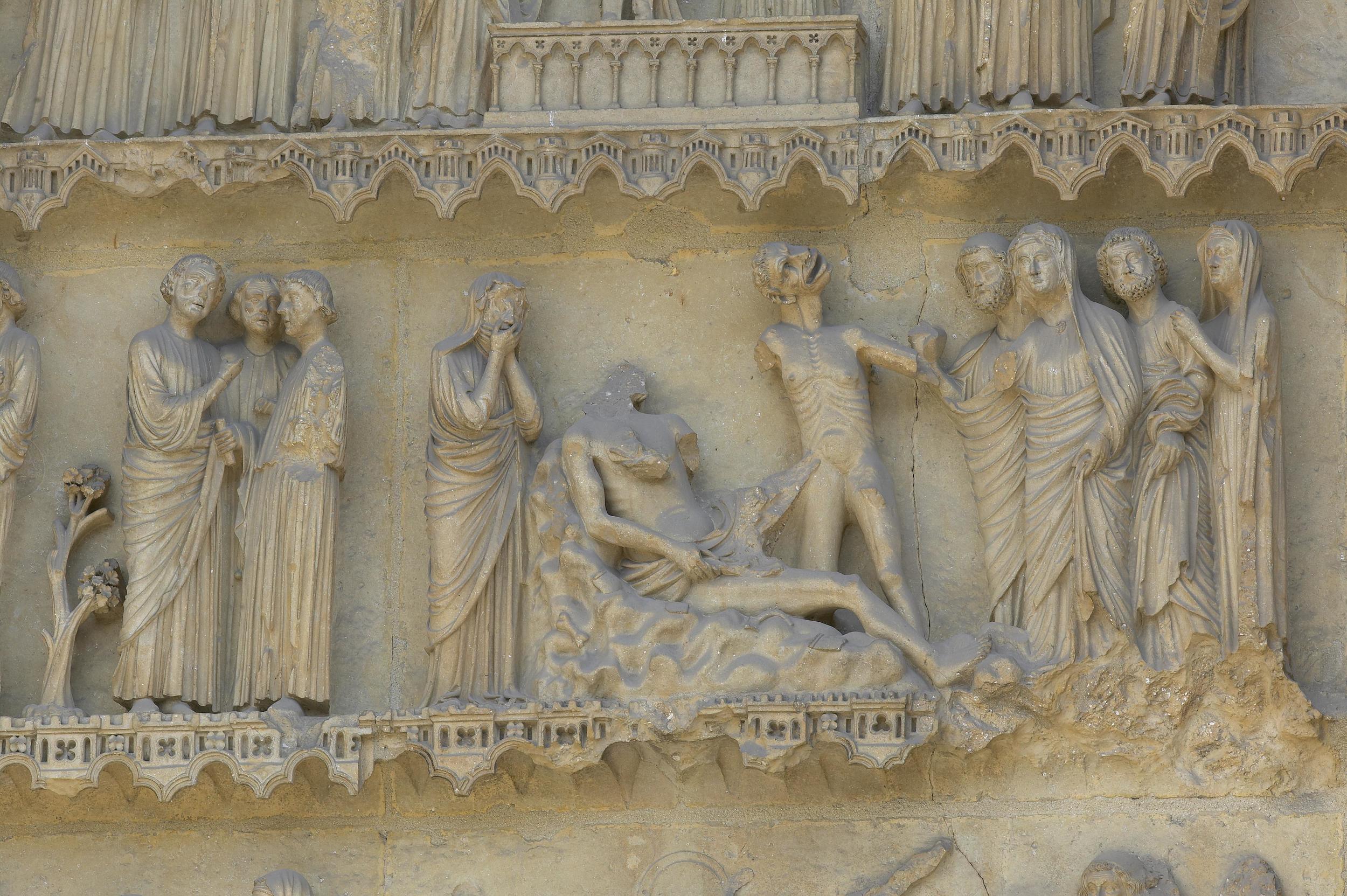

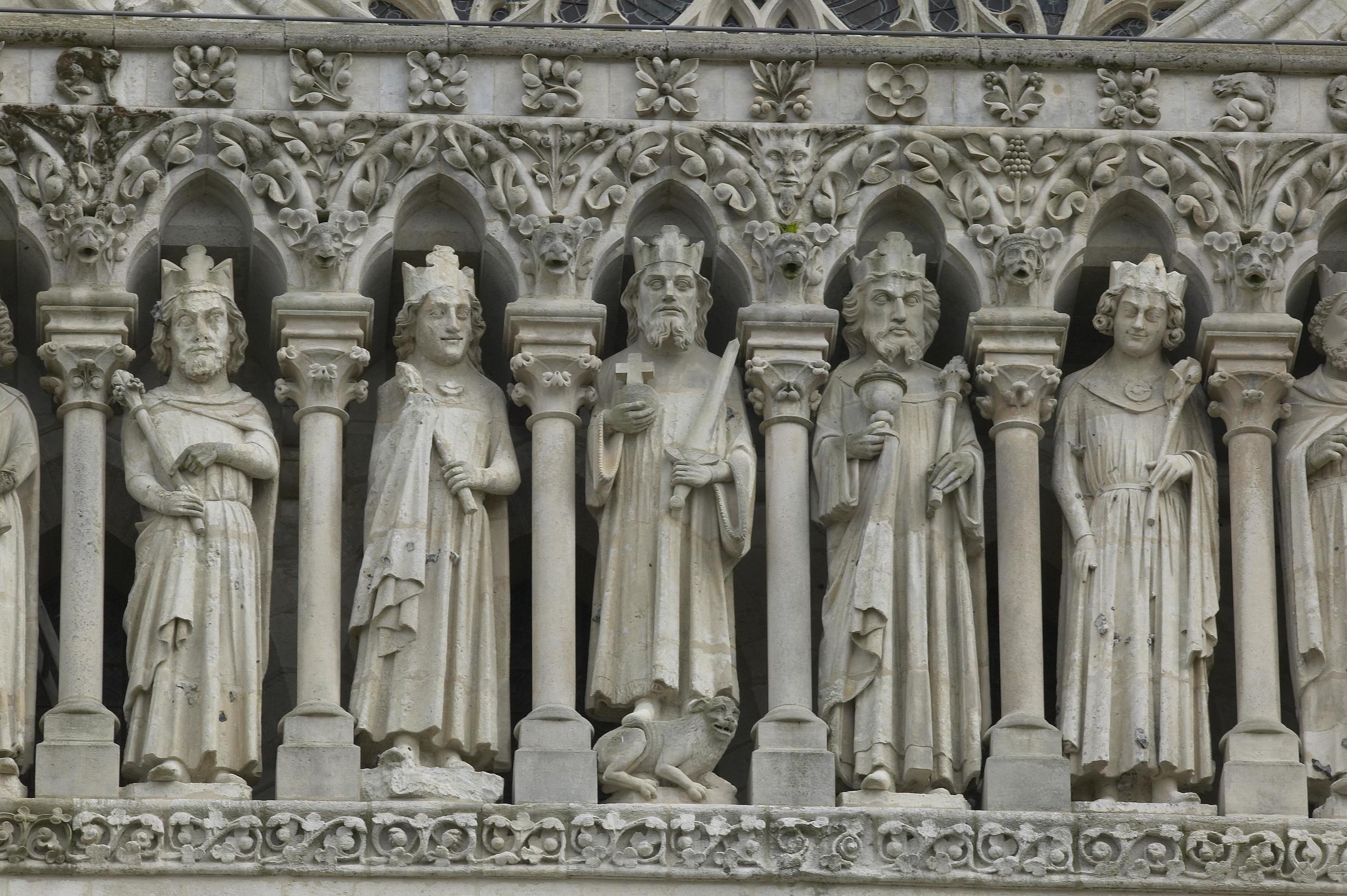

Amiens Cathedral, Gallery of Kings (photo credit: Steven Zucker)

The Lordship & Commune Project

The text Barbara Abou-El-Haj was incomplete, un-proofed, and in places a series of notes. We have done our best in this project to offer up the most refined parts of her work and fill in gaps. So the text on this site is a hybrid – of words written by Barbara Abou-El-Haj, and those composed by members of the collaboratory team, aiming to capture the spirit and approach of the original author.

Editors and Organizers of the Work

This project has been developed at the invitation and with the support of Barbara Abou-El-Haj’s husband, Rifa’at Abou-El-Haj, and her two daughters, Sarra Fleur and Marriam, as well as two close friends, Kathryn Sklar and Tom Dublin (both professors and colleagues of Barbara’s at SUNY Binghamton).

Editors and Organizers of the work:

· Michael Davis, Professor, Mount Holyoke College

· Lindsey Hansen, PhD, Indiana University Bloomington

· Jennifer Feltman, Assistant Professor, University of Alabama

· Janet Marquardt, Distinguished Professor Emerita, Eastern Illinois University

· Nina Rowe, Associate Professor, Fordham University

The Lordship and Commune Project: Framing Questions

Barbara Abou-El-Haj envisioned her book to be comparative study of the cathedrals of Reims and Amiens, considering the monuments in relation to the local conditions in which they were planned and built. Focusing on the cathedrals in tandem with their regional political, social, and economic histories, Abou-El-Haj sought to dispel what she understood to be myths in the prevailing discourses on Gothic cathedrals – primarily that these structures were built with the consensus of their local towns and that they function as symbols of harmony, materializing an urgent and eager piety shared by burghers and cathedral authorities.

I. REIMS

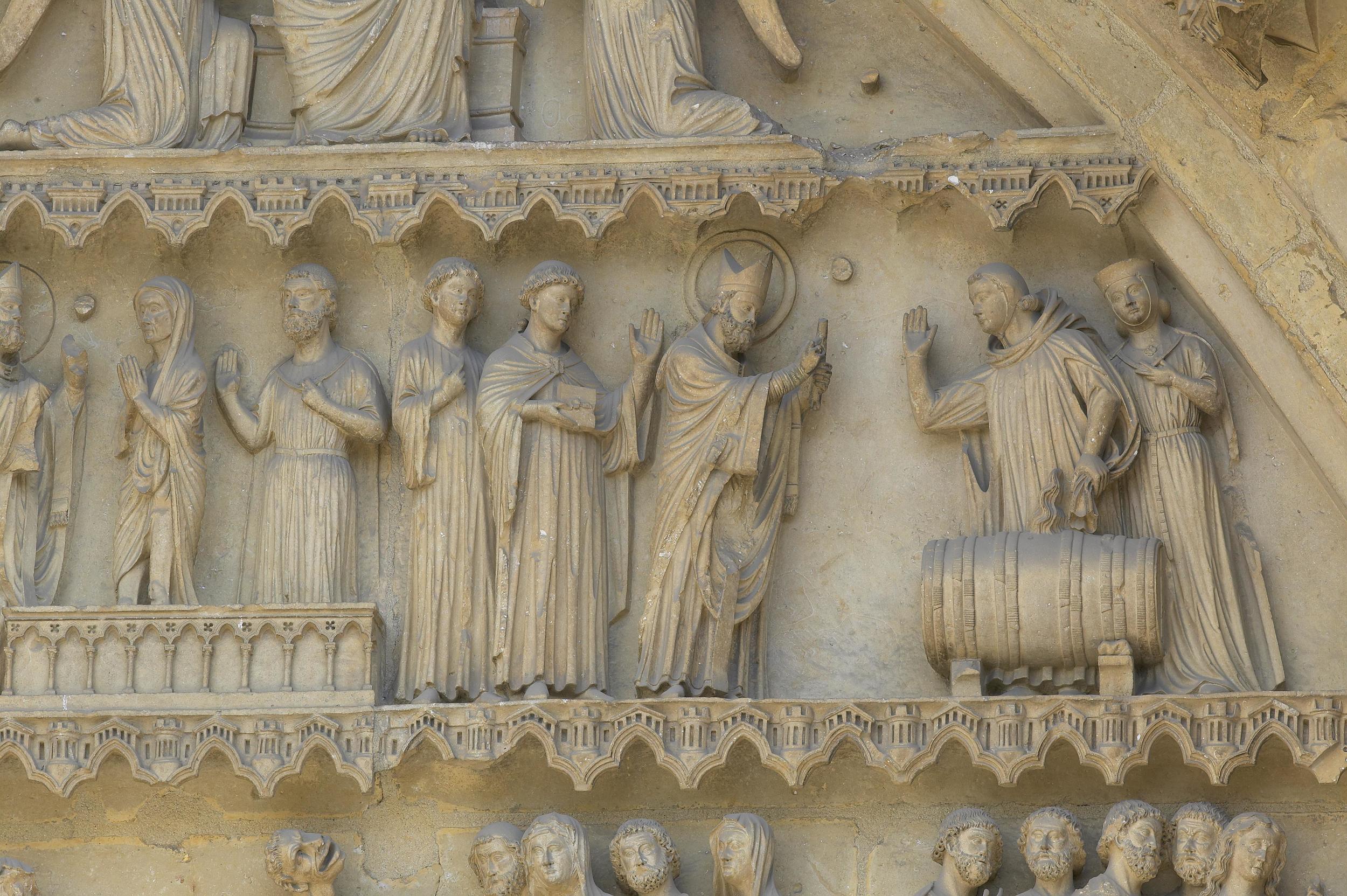

In the thirteenth century, the ecclesiastical hierarchy of Reims could justify the tremendous expense of materials and labor used in the construction and adornment of a new cathedral built in the Gothic style on the grounds that the town was the site of the origin of a Christian kingdom of France.

Unlike Picardy (the region that housed Amiens), where communes had been established early and often without violence, the metropolitan town of Reims remained seigneurial and its lords deeply resistant to burgher efforts to gain a charter of communal liberties.

Scholarly and popular accounts of the rebuilding of Reims Cathedral typically begin with a report of a fire in the existing structure on May 6, 1210 and the ceremonial laying of a cornerstone at the south façade one year to the day later.

When the Reims cathedral hierarchy quashed the urban insurrections of 1233 and 1238 [See Section I, pt. 3A] the clergy imposed huge reparations.

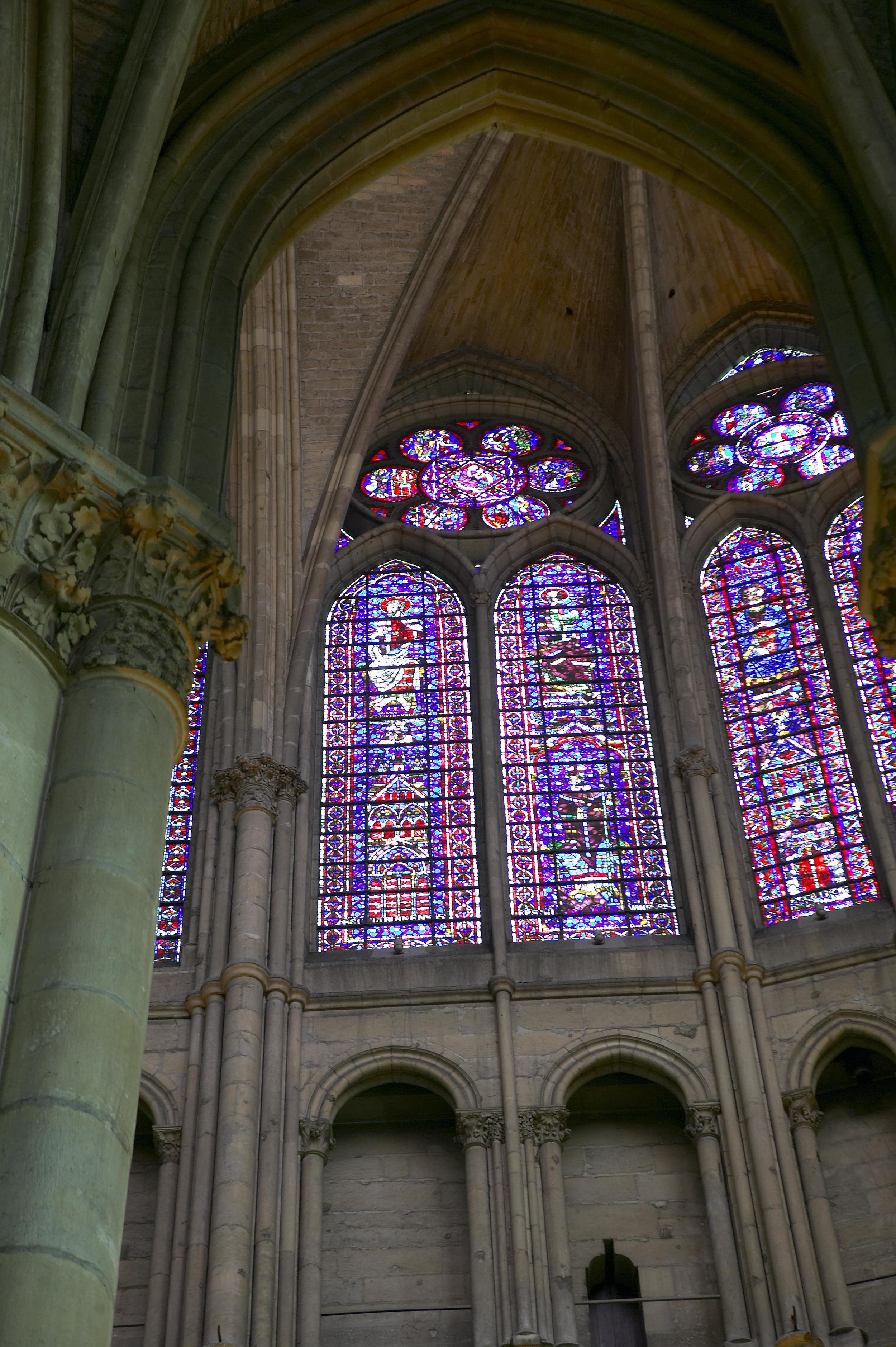

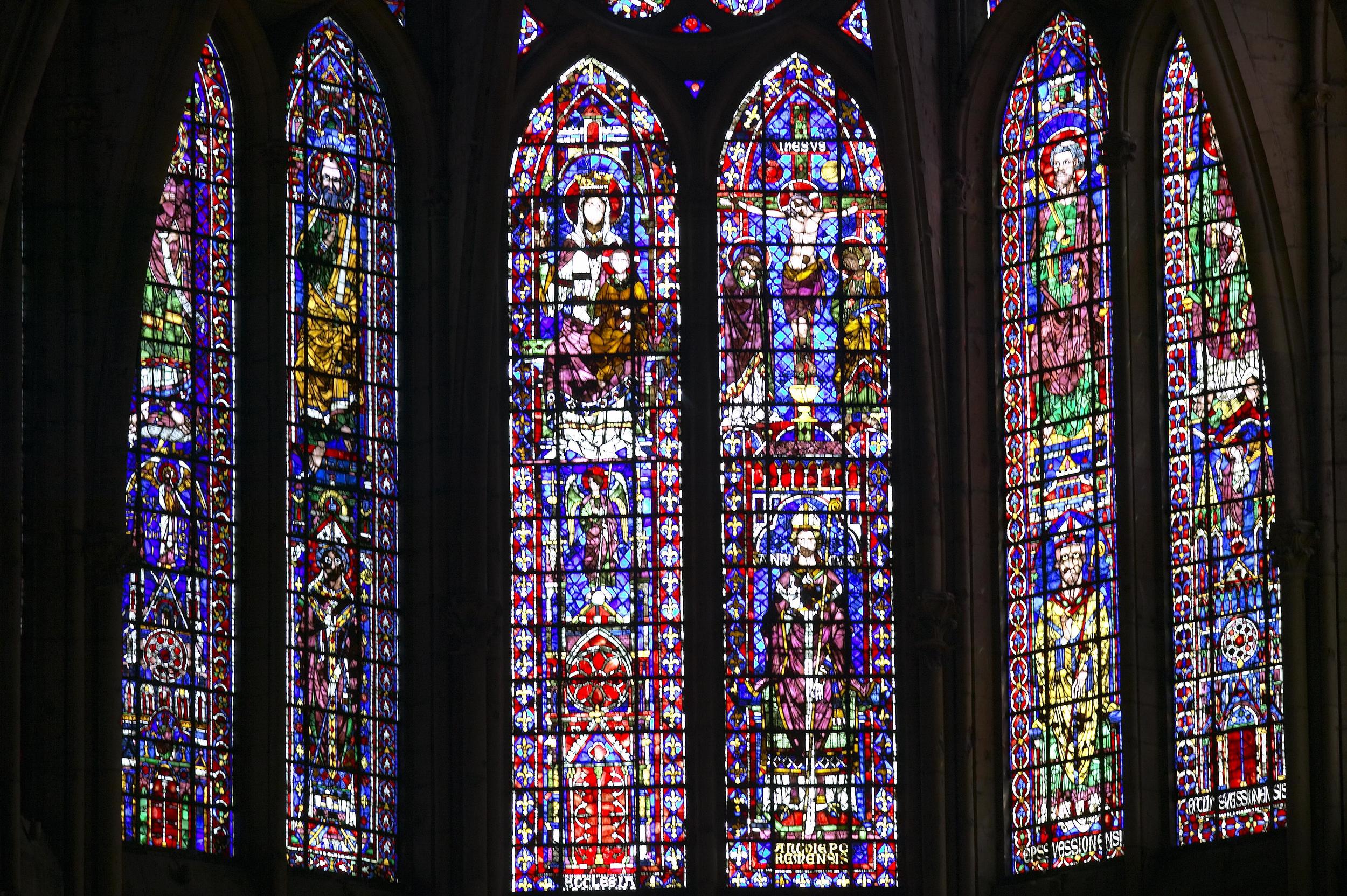

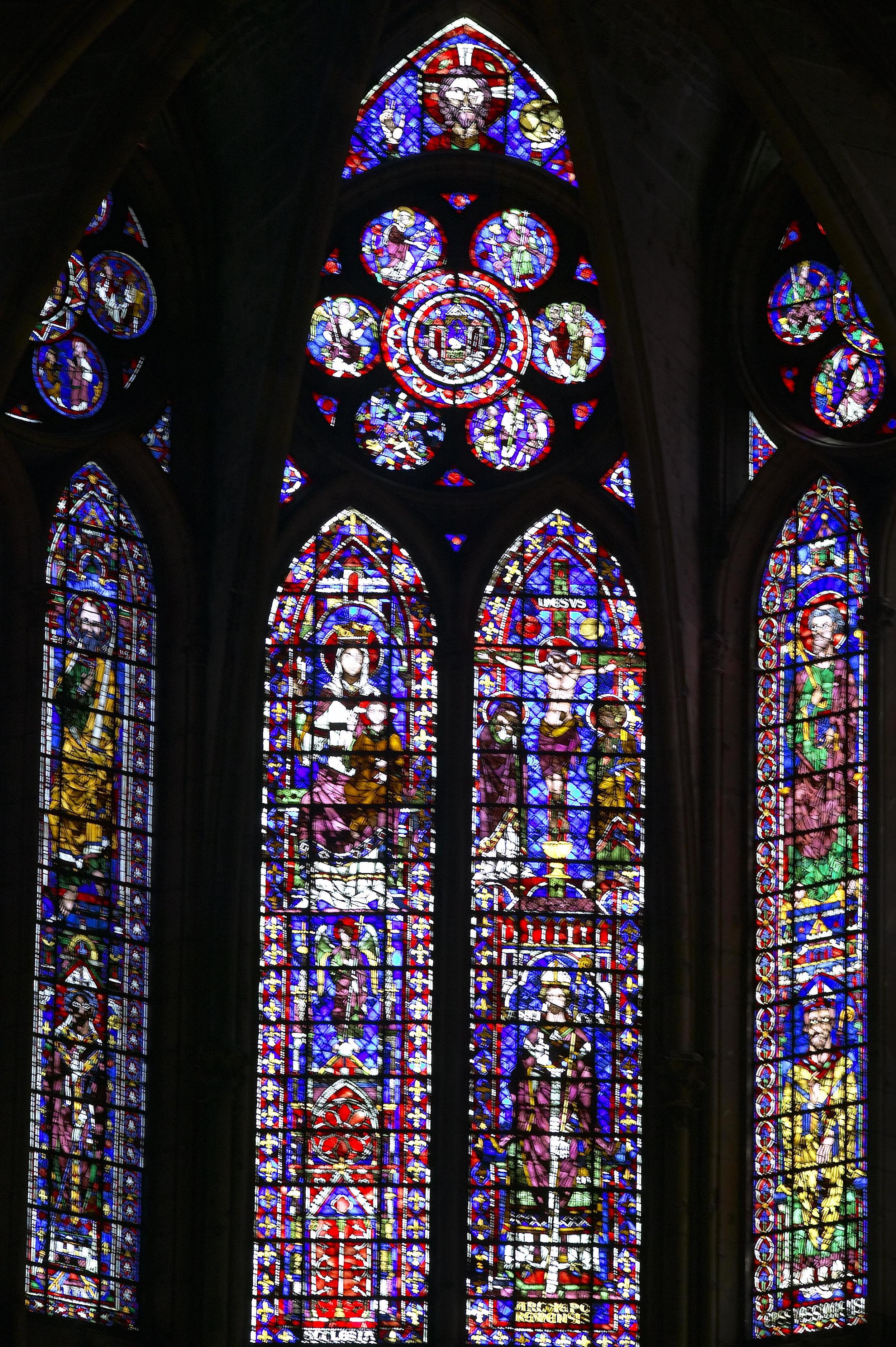

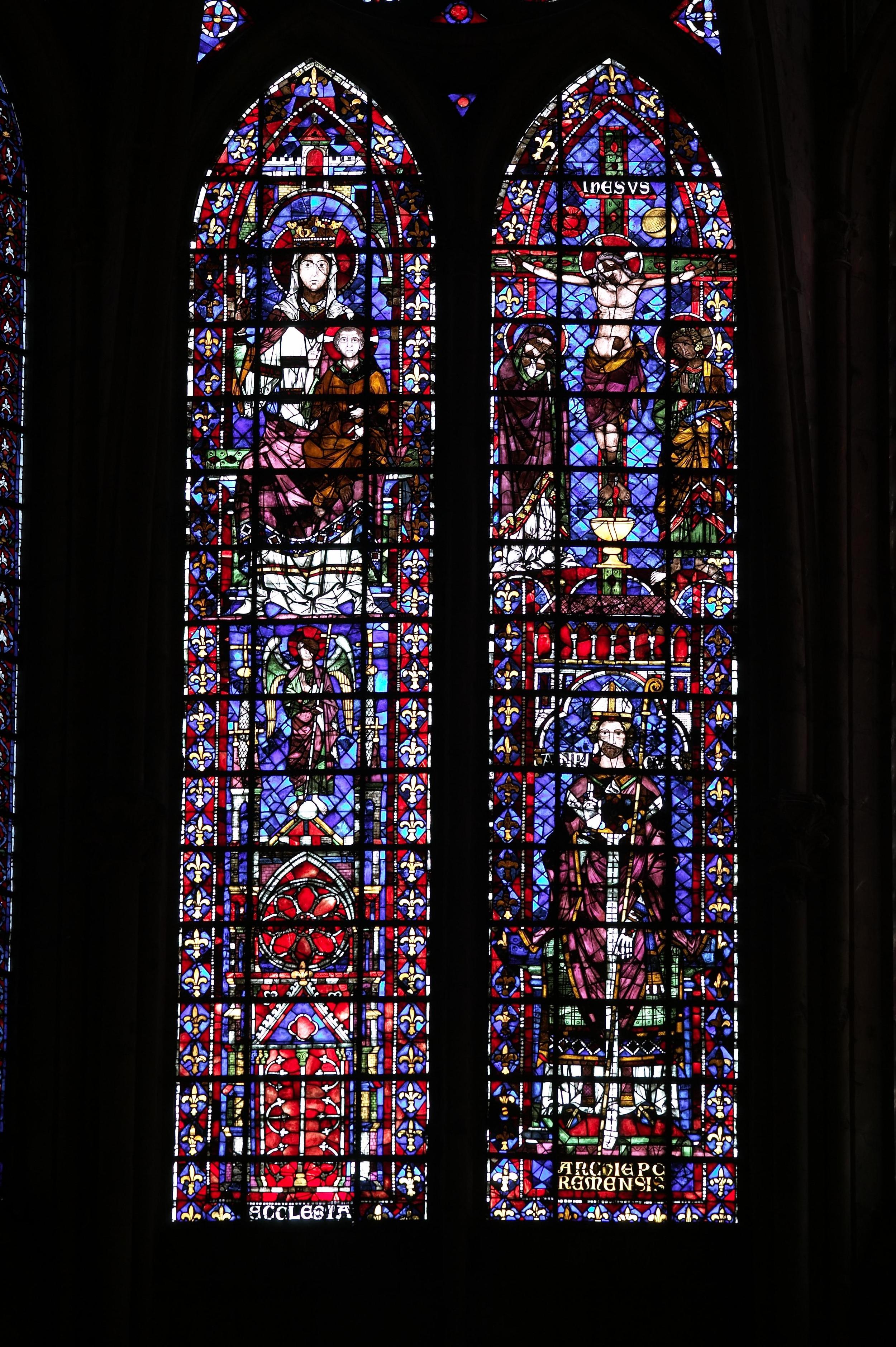

Stained glass was installed in the high choir of Reims Cathedral by 1241, in the years following the local rebellion, restoration of order, and exertion of clerical control in the city

The coronation has been the leading interpretive model for the Gothic cathedral of Reims. However, such a durable resolution is apparent only in retrospect.

II. AMIENS

The second part of Barbara Abou-El-Haj’s book was to address the ways in which the distinct socio-political structure of the city of Amiens affected the construction of the cathedral.

Drawing on the work of Ronald Hubscher, Pierre Desportes, and John S. Ott, Abou-El-Haj was to re-examine the role of history and collective memory in the projection of episcopal authority in the town of Amiens.

Abou-El-Haj sought to overturn the idea that the relations between the town of Amiens and the cathedral chapter in the thirteenth century were cooperative and consensual in regard to the construction of the cathedral.

Among founders of the Amiens commune were a group of wealthy men in service to the count or the bishop who had supervised or controlled monopolies from which they had amassed fortunes, and who seized communal power after 1117:

Barbara Abou-El-Haj left this portion of her analysis in inchoate form – an undeveloped series of notes, questions, and observations.

III. MODERN ERA

Barbara Abou-El-Haj envisioned a third section of her study on the medieval cathedrals of Reims and Amiens.

Abou-El-Haj sought to impress upon her readers that medieval churches have not always enjoyed their current prestige.

During the period of the Restoration, Charles X was crowned king at Reims (1824), but this was the last coronation to be held at Reims or anywhere else in France.

The cathedral of Amiens, relatively undamaged during the French Revolution, remained within its confined precinct.

GALLERY

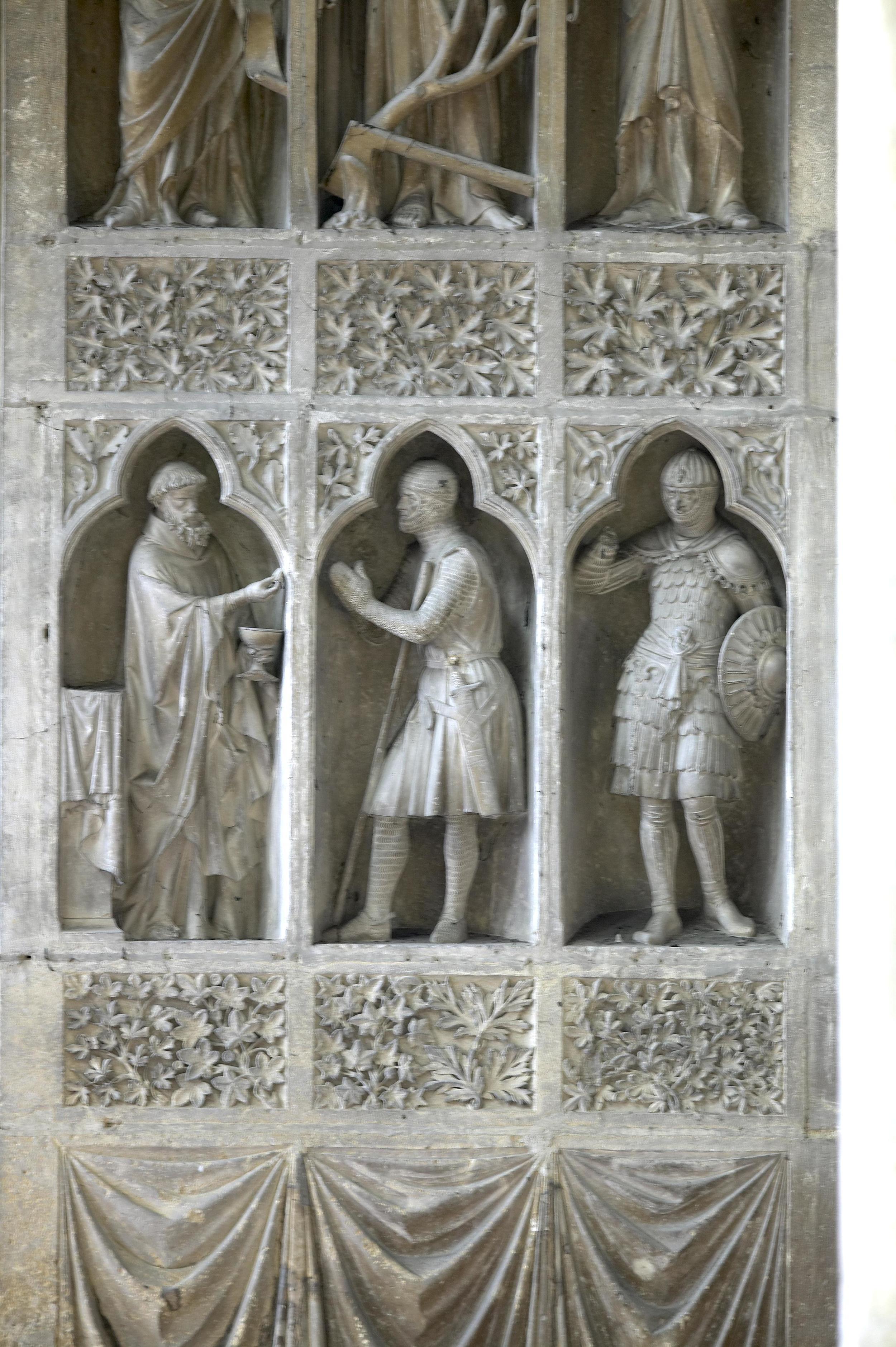

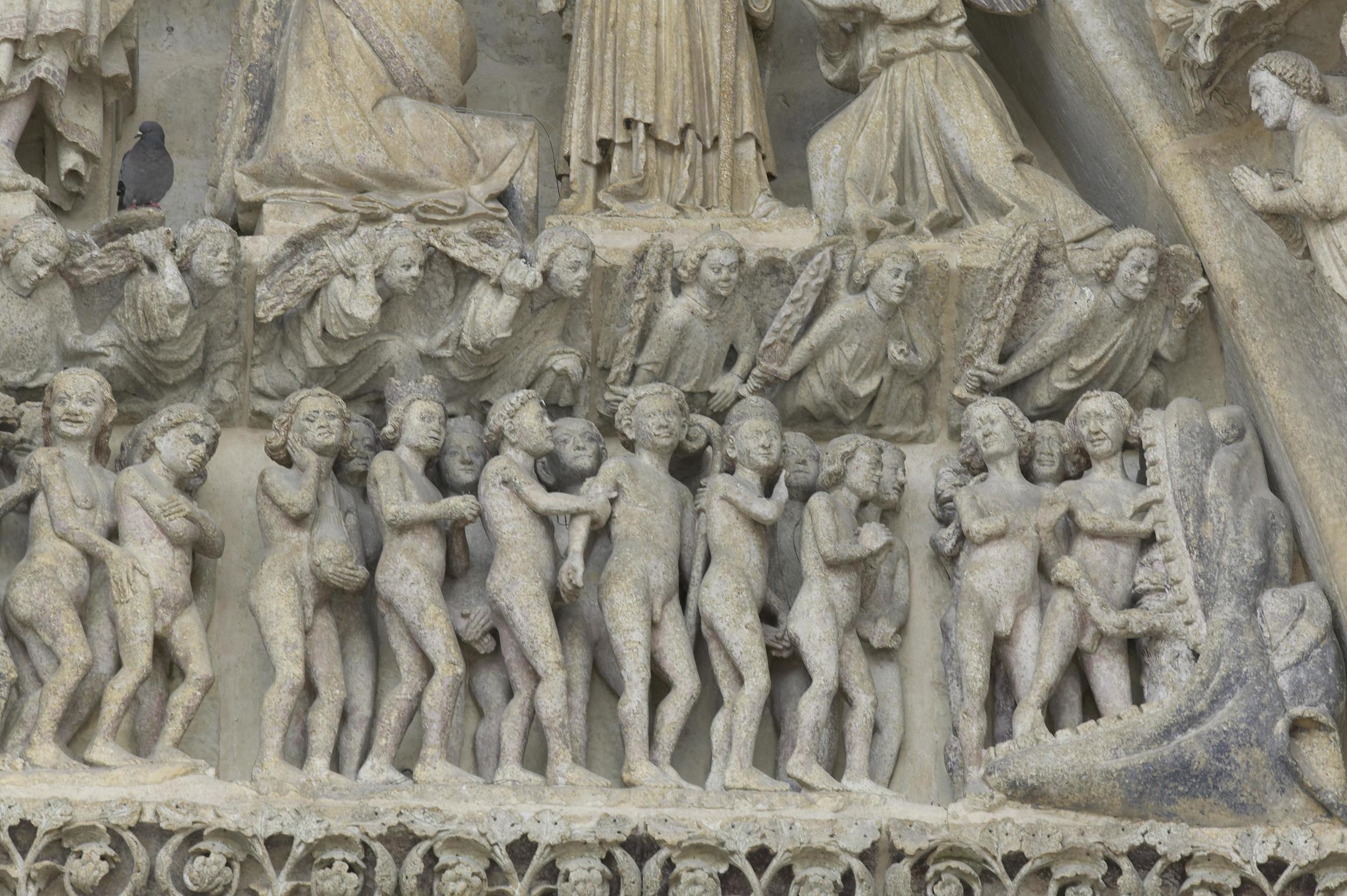

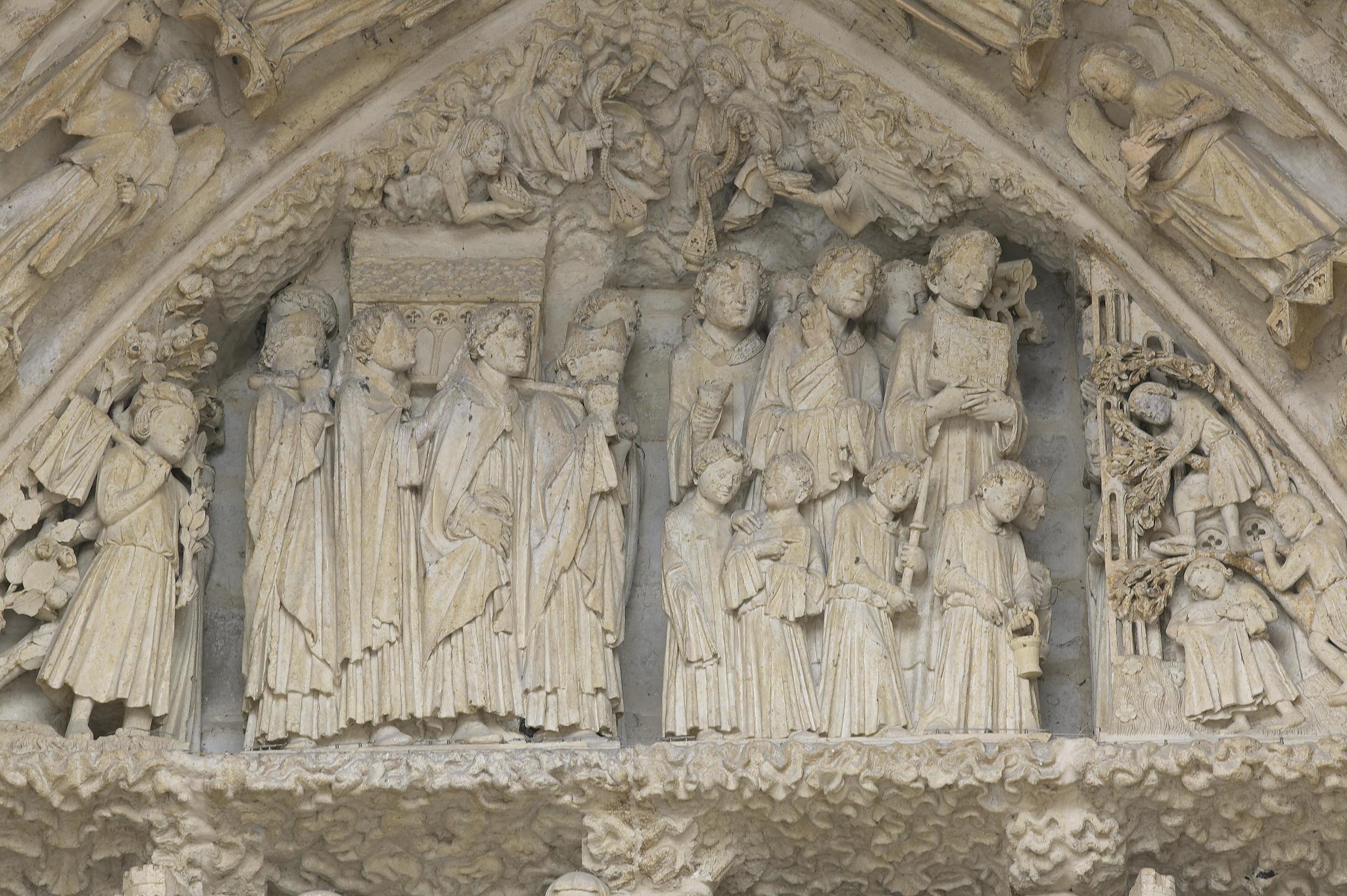

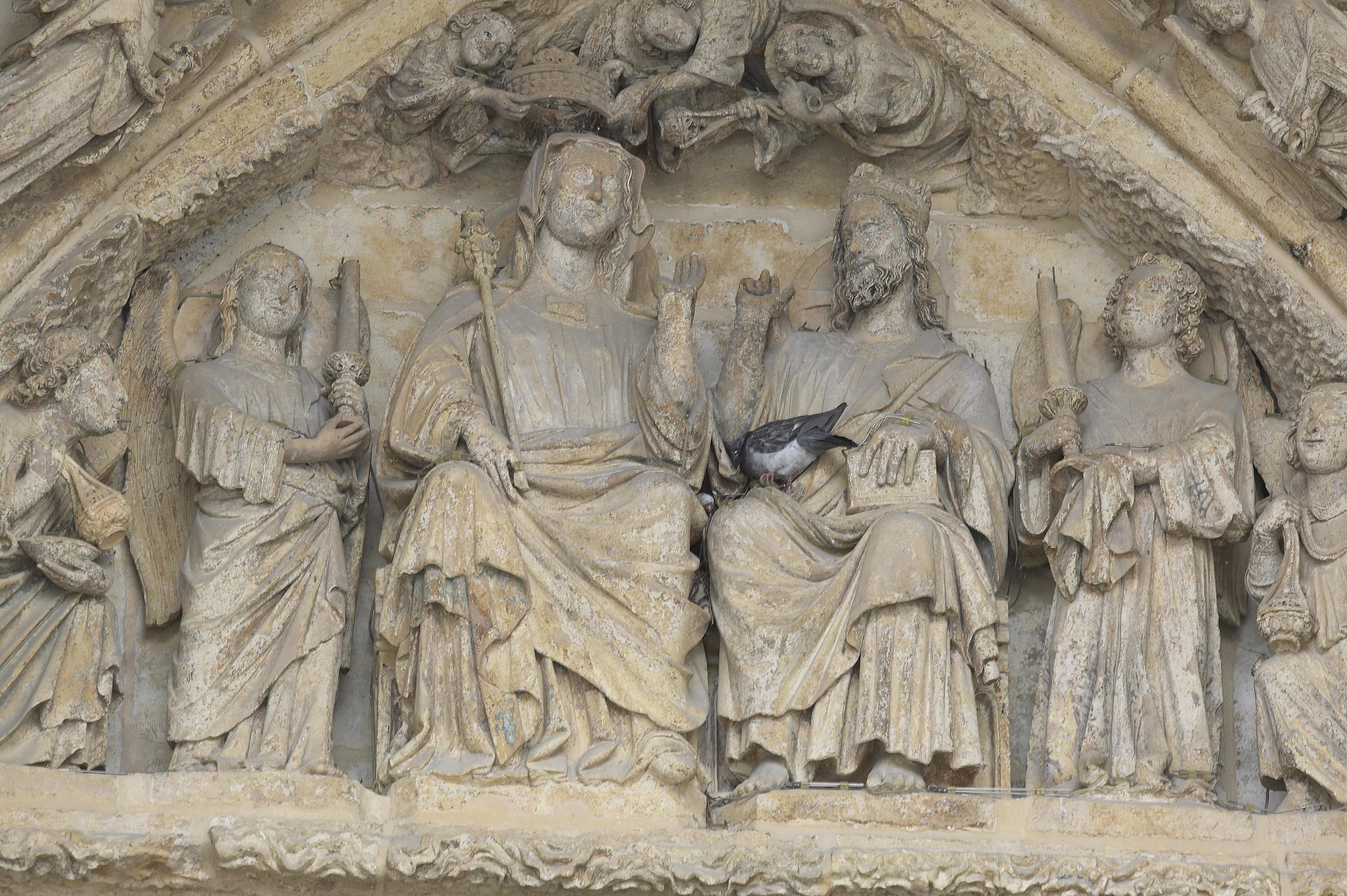

At her death on March 6, 2015, Barbara Abou-El-Haj left a book, long in the works, unfinished. Her title was Lordship and Commune: A Comparative History of Building and Decorating in Reims and Amiens. The book was to engage with the ways in which the differing political structures of the medieval cities of Reims and Amiens affected the construction of their respective Gothic cathedrals in the thirteenth century. Abou-El-Haj observed that scholars have noted the differences in the apparent quality and variety of sculptural decoration at Reims and Amiens but failed to consider the dissimilar political situations in the cities. The archdiocese of Reims was ruled by an autocratic archbishop-count, who held the power to levy taxes on its citizens, while Amiens, a suffragan of Reims, was a self-ruled commune independent of episcopal jurisdiction. She maintained that it was precisely the governmental differences at the sites and the resulting disparity of resources that were reflected in the buildings themselves.